Baiza v. State | How Slowly Should an Officer Read Miranda Warnings?

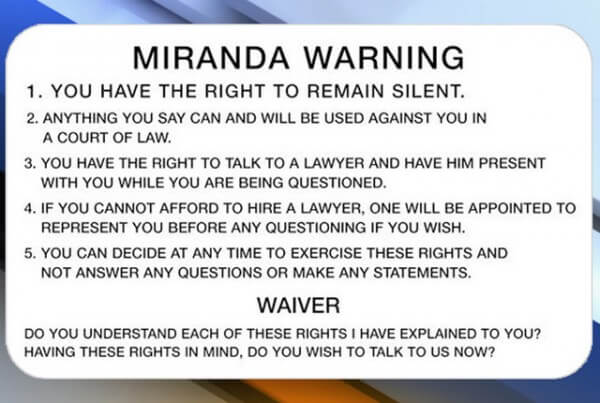

We all know that the police must read the Miranda warnings before they question someone that is under arrest. But what does that look like in a practical sense? Can the officer read the Miranda warnings like the side effect warnings in a prescription drug commercial, where we can’t understand them? Or does he have to read them slowly, ensuring that the person being questioned fully understands each provision? This issue recently came up in Baiza v. State, an appellate case in the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals.

We all know that the police must read the Miranda warnings before they question someone that is under arrest. But what does that look like in a practical sense? Can the officer read the Miranda warnings like the side effect warnings in a prescription drug commercial, where we can’t understand them? Or does he have to read them slowly, ensuring that the person being questioned fully understands each provision? This issue recently came up in Baiza v. State, an appellate case in the 11th Circuit Court of Appeals.

Gregory Baiza was convicted for sexual assault of his wife and sentenced to twelve years in prison. Baiza was in a common-law marriage with his wife and had two children together. There was an argument between the two when Baiza found out that his wife was pregnant with their third child. Baiza’s wife claims that Baiza forced himself on her after this argument. Eventually the police were called on the scene.

After Baiza’s wife left for the hospital, she decided to press charges on Baiza. A detective came over to get a statement from Gregory Baiza but he refused. The detective then placed Baiza under arrest. Baiza, however, admitted during the second recorded statement that his wife told him to stop but that he kept going – a statement that would ultimately lead to his conviction for rape at trial.

Baiza argued to the Eleventh Court of Appeals that this admission during the recorded statement should not have been allowed into evidence at the trial court. Baiza argued that when the detective read Baiza the Miranda warnings, he read them so fast that they were unintelligible. Specifically, Baiza argued that he did not hear the warning that he was allowed to terminate the interview at any time.

Strict Compliance with Miranda Rules Not Required, But the Reading of Rights Must be Intelligible

In reviewing this issue, the Eleventh Circuit notes that strict compliance with the Miranda rules is not required, but rather a “substantial compliance” will suffice. “Thus, the warnings given to an accused are effective even if not given verbatim, so long as they convey the ‘fully effective equivalent’ of the warnings.” In order for an admission to be allowed in court, the warnings must also be on the recording. The court listened to the recording to determine if the detective gave the prescribed warnings to Baiza. The detective read the warnings from a card to Baiza. The court slowed down the audio and determined that the detective did in fact inform Baiza that he has the right to terminate the interview. However, the Eleventh Circuit determined that when played at actual speed, the “right to terminate” warning is unintelligible.

The Eleventh Circuit determined that because the “right to terminate” warning was unintelligible, that the warnings were not given and that the trial court erred when it allowed the admission into evidence. The Court then went on to find that they did not have fair assurance that the error did not influence the jury or that the error influenced the jury only slightly by incorrectly allowing this admission into evidence. For these reasons, the Eleventh Circuit reversed the judgment and remanded for a new trial.

It is very difficult to get a case overturned, even when evidence has been incorrectly admitted. But here, the Court finds that even though the detective read Baiza his Miranda warnings, reading them so quickly as to make a key part unintelligible was enough to keep out an admission by Baiza from evidence. Specifically, the court finds that the “right to terminate” is a crucial part of the Miranda warnings and that a detective or officer cannot read them so quickly as to make them unintelligible or any admission shall not be admitted into evidence.

Read the full opinion in Baiza v. State.