“Sexting” has become a very popular activity amongst teenagers and young adults in the last several years. This generation sees it as just another ordinary part of life with cell phones. For parents, prosecutors, and law enforcement officers, however, sexting is a dangerous habit that has wide-ranging effects. While sexting has the potential to severely damage lives and reputations, the very nature of it makes it difficult for authorities to adequately address the problems it causes. This article will explore what sexting is, how common it is, the applicable laws, and the practical implications of applying those laws to common instances of sexting.

“Sexting” has become a very popular activity amongst teenagers and young adults in the last several years. This generation sees it as just another ordinary part of life with cell phones. For parents, prosecutors, and law enforcement officers, however, sexting is a dangerous habit that has wide-ranging effects. While sexting has the potential to severely damage lives and reputations, the very nature of it makes it difficult for authorities to adequately address the problems it causes. This article will explore what sexting is, how common it is, the applicable laws, and the practical implications of applying those laws to common instances of sexting.

What Is Sexting?

Sexting is derived from the words “sex” and “texting.” It means the sending of nude or sexually explicit photos or sexually suggestive text messages by text, email, or instant messenger using a mobile device. Many times, the person depicted in the photographs has either consented to the photo being taken or has taken the pictures of themselves. Typically, the person in the photograph, either on their own initiative or at the request of another, takes the photo and then voluntarily sends it to a significant other or a person they are attracted to. The intent is generally for the picture to be kept private by the initial recipient.

The problem with sexting arises when the photograph is either posted on the internet, usually through a social media platform, or is shared with others through text or email. In many cases, this posting or sharing is not consented to by the person depicted in the picture.

How Common is Sexting?

A study done by Drexel University in 2015 found that over 80% of adults surveyed admitted to sexting within the last year. The study was presented during the American Psychological Association’s 2015 convention. According to GuardChild.com, 20% of all teenagers have sent or posted nude or semi-nude photos or videos of themselves and 39% of teenagers have sent sexually suggestive messages through either email, text, or instant messaging.

Criminal Laws Applicable to Texting in Texas

In the State of Texas, there are several laws which could be used to prosecute instances of sexting, especially if it involves a minor. These laws can range from a Class C misdemeanor to a first-degree felony.

Unlawful Disclosure or Promotion of Intimate Visual Material

Texas law makes it unlawful for a person to intentionally disclose photographs or videos of a person engaged in sexual conduct or with their intimate parts exposed without the consent of the person depicted if the person in the photo/video had a reasonable expectation that the material would remain private, the person depicted is harmed and the identity of the person in the photo/video is revealed through the disclosure. This is a Class A misdemeanor.

Sale, Distribution, or Display of Harmful Material to a Minor

A person who sells, distributes, or shows “harmful material” to a minor, knowing that the material is harmful and the person is a minor, or displays harmful material and is reckless about whether a minor is present who would be offended is guilty of this offense in Texas. This is a Class A misdemeanor unless the person uses a minor to commit the offense, and then it is a third-degree felony.

Sexual Performance by a Child

The offense of sexual performance of a child is committed when a person employs, authorizes, or induces a child under the age of 18 to engage in sexual conduct. In this context, “sexual conduct” includes the lewd exhibition of the genitals, anus or breast. This offense is a third-degree felony, but if the victim was under the age of 14 at the time of the offense, then it is enhanced to a second-degree felony.

Possession or Promotion of Child Pornography

A person commits the offense of possession or promotion of child pornography if he intentionally or knowingly promotes or possesses with the intent to promote material that depicts a child engaged in sexual conduct knowing that the material depicts a child. This is a third-degree felony, but it can be enhanced to a second or first-degree felony.

The Sexting Law – Electronic Transmission of Certain Visual Material Depicting Minor

This is Texas’ “sexting” statute. Under it, a person under the age of 18 commits an offense if he intentionally or knowingly possesses or promotes to another minor visual material that depicts a minor engaged in sexual conduct by electronic means if he produced the material or knows that another minor produced it. This is a Class C misdemeanor, but it can be enhanced to either a Class B or Class A misdemeanor in certain situations.

Practical Implications

An instance of sexting in Texas can be prosecuted under any of the above laws. However, there are problems with each of these statutes that makes it difficult to prosecute sexting cases under them. These problems are what led the Texas legislature to create the sexting law several years ago.

Problems with the Sexting Law

However, there are two major problems with this law. First, the sexting statute only applies to persons under the age of 18. This means that an 18-year-old high school student who shares sexting photos with others in his high school cannot be prosecuted under this law. The second problem with it is that it creates a defense to prosecution if the person in possession of the visual material destroys it. So, the law that makes sexting illegal also allows those who break the law to get away with it by destroying the evidence. Because of these problems, it is almost impossible to prosecute someone under this law.

Problems with Using the Other Laws to Prosecute Sexting

The main issue with using the other laws laid out above to prosecute sexting cases is that they were not created to address this specific behavior. So, it becomes a situation where prosecutors are having to shove a square peg into a round hole to make it work in many cases. For instance, the Unlawful Disclosure or Promotion of Intimate Visual Material law requires that the person in the pictures had a reasonable expectation that the photos would remain private. GuardChild.com found in their compilation of sexting statistics that 44% of teenagers believe it is common for sexually suggestive text messages to be shared with others, and 35-40% of them feel that it is common for nude or semi-nude photos to be shared with others beyond the intended recipient. These beliefs undermine the “reasonable expectation of privacy” prong of the law.

Similarly, the Possession or Promotion of Child Pornography statute is problematic when used in sexting cases because it does not include any protections from prosecution for the victim. This means that when a teen age girl takes a nude photo of herself and sends it to her boyfriend, who then shares it with other students, the girl who took the photo of herself is as guilty of promotion of child pornography as the boy who shared it with others. Most people would agree that the victim shouldn’t face charges for child pornography. Yet, prosecutors must either prosecute both of them or do nothing.

Sex Offender Registration for a Sexting Conviction

Another major practical ramification of sexting is that if a person is convicted or adjudicated for sexting under the possession or promotion of child pornography law, he will be required to register as a sex offender for life if the person is prosecuted in the adult system or for ten years past the end of his sentence if he is adjudicated as a juvenile. Depending on the facts of the case, this can be a very harsh consequence for a behavior that is so common in this modern world we live in. But it is important for anyone who engages in sexting, and their parents, to realize that sex offender registration for life is a very real possibility if prosecuted.

Conclusion

While many parents may not know that sexting even exists, the fact remains that it is much more common than we would like to think. It can have devastating consequences for the person depicted in the photos, and for anyone who shares or possesses these photos. Many teenagers engage in this behavior without realizing what the ramifications can be.

This is one area where the law hasn’t caught up to technology yet. So, the job of protecting our children from the harms associated with sexting still falls primarily to parents. It is important for parents to educate themselves about the practice and then talk to their teenagers and pre-teens about the dangers of sexting.

Fort Worth Sexual Crimes Defense Attorney

Rating: ★★★★★ 5 / 5 stars

Rated By Google User

“This firm was a Godsend in handling our case!”

If you’ve been a licensed (or even unlicensed) driver in Texas for long enough, you’ve experienced a traffic stop. Whether it be for speeding or something worse, a traffic stop is not generally a pleasant experience. But in some traffic stops across the state (hopefully not yours), the police conduct a search of the vehicle, then a search of the driver or passengers, and, finally make an arrest of some sort. How does something like a broken tail light or speeding lead to search, seizure, and arrest? When traffic stops for minor infractions potentially lead to serious criminal charges, it’s important to know how Texas courts define the moment when a traffic stop ends.

If you’ve been a licensed (or even unlicensed) driver in Texas for long enough, you’ve experienced a traffic stop. Whether it be for speeding or something worse, a traffic stop is not generally a pleasant experience. But in some traffic stops across the state (hopefully not yours), the police conduct a search of the vehicle, then a search of the driver or passengers, and, finally make an arrest of some sort. How does something like a broken tail light or speeding lead to search, seizure, and arrest? When traffic stops for minor infractions potentially lead to serious criminal charges, it’s important to know how Texas courts define the moment when a traffic stop ends.

“Sexting” has become a very popular activity amongst teenagers and young adults in the last several years. This generation sees it as just another ordinary part of life with cell phones. For parents, prosecutors, and law enforcement officers, however, sexting is a dangerous habit that has wide-ranging effects. While sexting has the potential to severely damage lives and reputations, the very nature of it makes it difficult for authorities to adequately address the problems it causes. This article will explore what sexting is, how common it is, the applicable laws, and the practical implications of applying those laws to common instances of sexting.

“Sexting” has become a very popular activity amongst teenagers and young adults in the last several years. This generation sees it as just another ordinary part of life with cell phones. For parents, prosecutors, and law enforcement officers, however, sexting is a dangerous habit that has wide-ranging effects. While sexting has the potential to severely damage lives and reputations, the very nature of it makes it difficult for authorities to adequately address the problems it causes. This article will explore what sexting is, how common it is, the applicable laws, and the practical implications of applying those laws to common instances of sexting.

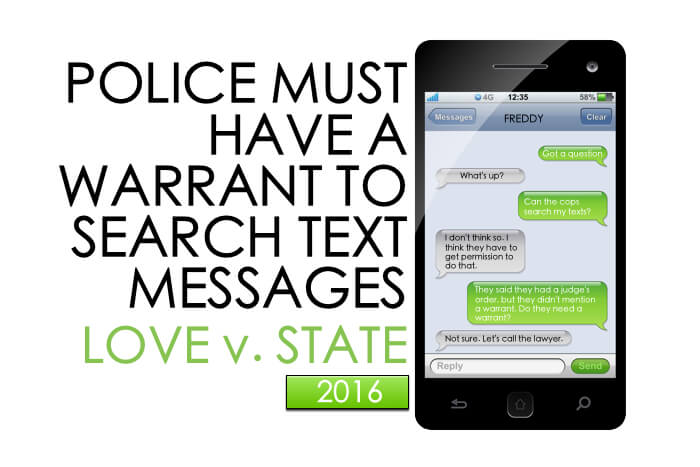

From call logs, to cell tower info, to sent and received text messages, many criminal investigations involve the contents of a defendant’s cell phone. Under the

From call logs, to cell tower info, to sent and received text messages, many criminal investigations involve the contents of a defendant’s cell phone. Under the

The juvenile justice system is a hybrid system. Juvenile proceedings are technically civil in nature, but they incorporate many elements from the criminal system. The reason for this separate system is to teach children that they will be held responsible for their actions without labeling them as criminals. The differences between adult and juvenile trials is a direct result of this difference in systems.

The juvenile justice system is a hybrid system. Juvenile proceedings are technically civil in nature, but they incorporate many elements from the criminal system. The reason for this separate system is to teach children that they will be held responsible for their actions without labeling them as criminals. The differences between adult and juvenile trials is a direct result of this difference in systems.

In the Texas juvenile justice system, a juvenile court has jurisdiction over a youthful offender if he or she is under the age of 17 at the time an offense is committed. The punishment for an offense typically can only last until a juvenile’s 19th birthday. We are often asked, “What happens if the juvenile is convicted of a serious offense? Is it possible for the court to impose a sentence that extends beyond the juvenile’s 19th birthday?” That is where Determinate Sentencing comes in. This post explains what Determinate Sentencing means and how it can impact a juvenile case.

In the Texas juvenile justice system, a juvenile court has jurisdiction over a youthful offender if he or she is under the age of 17 at the time an offense is committed. The punishment for an offense typically can only last until a juvenile’s 19th birthday. We are often asked, “What happens if the juvenile is convicted of a serious offense? Is it possible for the court to impose a sentence that extends beyond the juvenile’s 19th birthday?” That is where Determinate Sentencing comes in. This post explains what Determinate Sentencing means and how it can impact a juvenile case.

You may have heard of sleepwalking, or sleeptalking, but what about sleep sex? The idea of sleep sex or “sexsomnia” is typically worth a few laughs when you first hear about it, but it is a

You may have heard of sleepwalking, or sleeptalking, but what about sleep sex? The idea of sleep sex or “sexsomnia” is typically worth a few laughs when you first hear about it, but it is a

Are there any options for my child short of going to court? Many parents ask this question after finding out that their child has been referred to the juvenile system. For a lot of kids who are in trouble for the first time, there is a great option available: Deferred Prosecution Program (DPP). In Tarrant County, DPP is used quite often. This article will answer all of your questions about DPP.

Are there any options for my child short of going to court? Many parents ask this question after finding out that their child has been referred to the juvenile system. For a lot of kids who are in trouble for the first time, there is a great option available: Deferred Prosecution Program (DPP). In Tarrant County, DPP is used quite often. This article will answer all of your questions about DPP.

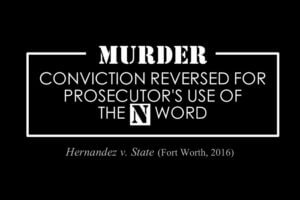

In December of 2014, Appellant Luis Miguel Hernandez was convicted of the murder of Devin Toler, an African-American man. During the trial, Appellant claimed self-defense, arguing that Toler attacked him and that by killing him, he was defending himself from the attack. The prosecution, however, presented evidence that Appellant provoked Toler by his words, some of them racial slurs. The actual words of the alleged racial slurs were never presented to the jury in the testimony of any witness or otherwise. However, during closing argument, the prosecutor said the following:

In December of 2014, Appellant Luis Miguel Hernandez was convicted of the murder of Devin Toler, an African-American man. During the trial, Appellant claimed self-defense, arguing that Toler attacked him and that by killing him, he was defending himself from the attack. The prosecution, however, presented evidence that Appellant provoked Toler by his words, some of them racial slurs. The actual words of the alleged racial slurs were never presented to the jury in the testimony of any witness or otherwise. However, during closing argument, the prosecutor said the following: