Do You Have a Fourth Amendment Privacy Interest in Your Bitcoin Transactions?

No, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals recently held that people do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the information (1) contained on the Bitcoin blockchain and (2) that you provide to cryptocurrency exchanges.1 The Court reached this decision through an analysis of the facts under the “third party doctrine” of Fourth Amendment jurisprudence. This doctrine is explained in further detail below.

No, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals recently held that people do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the information (1) contained on the Bitcoin blockchain and (2) that you provide to cryptocurrency exchanges.1 The Court reached this decision through an analysis of the facts under the “third party doctrine” of Fourth Amendment jurisprudence. This doctrine is explained in further detail below.

Read full case HERE. US v. Gratkowski, 964 F.3d 307 (5th Cir. 2020).

First Off, what is Bitcoin?

Bitcoin is a “collection of concepts and technologies that form the basis of a digital money ecosystem.”2 More colloquially, the word “bitcoin” refers to a bitcoin—a unit of digital currency used to store and transmit value among participants in the bitcoin network. Bitcoin derives its value not from physical characteristics like gold or trust in a central authority like fiat money. Instead, bitcoin is backed by the cryptographic technology behind it.

Bitcoin is powered by open-source code known as blockchain, which creates a shared public ledger that is viewable by anyone. Each transaction is a “block” that is “chained” to the code, creating a permanent record of each transaction. In order to transfer anything in this world, you need to be able to send and receive your items to and from a certain location. Bitcoin is no different. Like an email, Bitcoin is transferred between locations on the internet called Bitcoin addresses. A Bitcoin address indicates the source or destination of a Bitcoin payment. The Bitcoin blockchain contains only the sender’s address, the receiver’s address, and the amount of bitcoin transferred. Bitcoin wallets provide these addresses and utilize software that allows you to securely send, receive, and store bitcoin in the bitcoin network.

The central tenet behind the creation of Bitcoin was that willing parties should be able to transact directly with each other without the need for a trusted third party.3 A large part of the value in that kind of decentralization is in the privacy that it assumes will accompany the transaction. However, as the use and influence of cryptocurrencies expands, so too does the need of law enforcement to crack down on the illicit activities of crypto users that our society finds to be reprehensible. Analyzing the block chain for evidence of crimes involving bitcoin inevitably means that information of bitcoin transactions will be collected. This kind of forensic analysis, aside from collecting information on whether the bitcoin was used for something illegal, “can include the collection of large amounts of personal information about a user’s spending habits [and] total holdings[.]”4 The natural question for criminal law attorneys is whether a bitcoin user has a Fourth Amendment privacy interest in the information related to their bitcoin transactions.

Bitcoin Transactions and the 4th Amendment

The Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals in United States v. Gratkowski recently held that individuals do not have a Fourth Amendment privacy interest the information related to their bitcoin transactions.5 More specifically, the court found that there is no Fourth Amendment privacy interest in: (1) information on the bitcoin blockchain itself, and (2) bitcoin transactions in virtual currency exchanges.6

Gratkowski became the subject of a federal investigation when federal agents began investigating a child-pornography website. Users like Gratkowski paid the website bitcoin in exchange for downloadable child pornography. As mentioned above, the bitcoin blockchain only contains the sender’s address, the receiver’s address, and the amount of bitcoin transferred between the two parties. The identity of the owners do not appear on the bitcoin blockchain, but it is possible to discover the owner of a bitcoin address by analyzing the blockchain:

“For example, when an organization creates multiple Bitcoin addresses, it will often combine its Bitcoin addresses into a separate, central Bitcoin address (i.e., a “cluster”). It is possible to identify a “cluster” of Bitcoin addresses held by one organization by analyzing the Bitcoin blockchain’s transaction history. Open source tools and private software products can be used to analyze a transaction.”7

Federal agents used an outside service to analyze the publicly viewable bitcoin blockchain and identify a cluster of bitcoin addresses controlled by the website.8 They then served a grand jury subpoena on Coinbase (a prominent cryptocurrency exchange) for all information the exchange had on the Coinbase customers whose accounts sent Bitcoin to any of the addresses in the child-pornography website’s cluster. Coinbase turned over Gratkowski’s information, and federal agents obtained a warrant to search Gratkowski’s house. The agents found a hard drive containing child pornography and subsequently charged Gratkowski with one count of receiving child pornography and one count of accessing websites with intent to view child pornography.

At trial, Gratkowski moved to suppress the evidence the government obtained under the warrant, arguing that both the subpoena to Coinbase and the analysis done on the blockchain violated the Fourth Amendment. For the government to infringe upon an individual’s Fourth Amendment protection against unreasonable searches, the person must have a “reasonable expectation of privacy” in the items obtained.9 The “third-party doctrine” instructs that a person generally “has no legitimate expectation of privacy in information he voluntarily turns over to third parties.”10

For instance, the Supreme Court in United States v. Miller held that bank records were not subject to Fourth Amendment Protections.11 The Court also held that telephone call logs were not subject to Fourth Amendment protections because the telephone numbers we dial are voluntarily conveyed to the phone company when we place a call.12 However, the Supreme Court recently held that individuals do have a privacy interest in their cell phone location records, despite the records being held by a third party.13 In deciding this, the Court set-up the current framework under which courts are to determine whether the third-party doctrine applies to certain information that is shared with third parties: The sole act of sharing the information is no longer determinative as to whether we have a Fourth Amendment privacy interest in it. Rather, courts are to consider, “‘(1) the nature of the particular documents sought,’ which includes whether the sought information was limited and meant to be confidential, and (2) the voluntariness of the exposure.”14

The Fifth Circuit reasoned that the information on the Bitcoin blockchain is more similar to bank records and telephone call logs than to cell phone location records.15 The court held that the information contained on the Bitcoin blockchain (the amount of Bitcoin transferred and the Bitcoin addresses of the sender and receiver) is limited, and Bitcoin users are unlikely to expect that information to be kept private as it is well known that it is recorded on the publicly available blockchain.16 The court also reasoned that the public exposure of this information is voluntary because transferring and receiving Bitcoin requires an affirmative act by the Bitcoin address holder.17 The Fifth Circuit therefore held that there is no reasonable expectation of privacy in the information contained on the Bitcoin blockchain.18

The Court used similar reasoning regarding the question of privacy in the Bitcoin transactions on Coinbase. Coinbase is a financial institution like a bank. Both are subject to the Bank Secrecy Act as regulated financial institutions, and both keep records of customer identities and currency transactions. The Court held that, “[h]aving access to Coinbase records does not provide agents with ‘an intimate window into a person’s life’; it provides only information about a person’s virtual currency transactions.”19 The court also held that, “[s]econd, transacting Bitcoin through Coinbase or other virtual currency exchange institutions requires an ‘affirmative act on the part of the user[,]’ which speaks to the voluntariness with which the information was turned over to Coinbase.20

Conclusion

The Gratkowski decision makes it difficult to imagine any situation in which a court would find there to be a Fourth Amendment privacy interest in information on the Bitcoin blockchain itself. Although Bitcoin users may truly value and believe in the privacy considerations contained in the monetary philosophy of Bitcoin, there is no getting around the fact that a “block” on the blockchain requires two Bitcoin addresses and the amount of bitcoin exchanged. And as long as private blockchain analytics companies continue to analyze only that information in determining the identity of Bitcoin users, courts will likely continue to find there to be no Fourth Amendment privacy interest in that information.

There appears to be more room to work with when it comes to cryptocurrency exchanges. Perhaps a court could find there to be a privacy interest in information given to an exchange whose business centers around user confidentiality. However, exchanges must comply with the same federal financial laws that govern Coinbase, and the record-keeping requirements under those laws would likely provide for a strong analogy to the Gratkowski case.

ENDNOTES:

1. United States v. Gratkowski, 964 F.3d 307 (5th Cir. 2020).

2. A. M. Antonopoulos, Mastering bitcoin: Programming the open blockchain (2nd ed.). Beijing etc.: O’Reilly.

3. Satoshi Nakamoto, Bitcoin: A Peer-to-Peer Electronic Cash System, https://bitcoin.org/bitcoin.pdf (2008).

4. Sasha Hodder & Rafael Yakobi, Bitcoin Fungibility, Mixing and the Legal Limits on Maintaining Privacy, https://bitcoinmagazine.com/culture/bitcoin-fungibility-mixing-and-the-legal-limits-on-maintaining-privacy (2020).

5. Gratkowski, 964 F.3d 307 (5th Cir. 2020).

6. Id.

7. Id. at 309.

8. Private blockchain analytics companies also provide services of this nature to cryptocurrency exchanges to help the exchanges meet their obligations under federal money laundering laws. See footnote 4 on the previous page for a discussion of privacy and these laws.

9. United States v. Jones, 565 U.S. 400, 406 (2012).

10. Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735, 743–44 (1979).

11. United States v. Miller, 425 U.S. 435, 439-40 (1976).

12. Smith v. Maryland, 442 U.S. 735, 743-44 (1979).

13. Carpenter v. United States, 138 S. Ct. 2206, 2217 (2018).

14. Gratkowski (quoting Carpenter, at 2219-20).

15. Id., at 311.

16. Id. at 312.

17. Id.

18. Id.

19. Id. (quoting Carpenter, at 2217).

20. Id. (quoting Carpenter, at 2220).

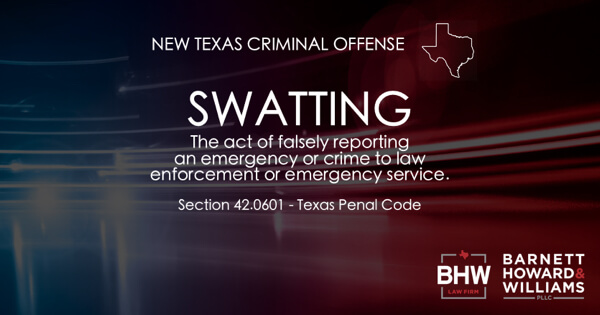

Texas legislators enacted several new criminal laws in the 2021 legislative session. Below, we highlight one of them – Swatting. Being from Texas, I initially thought this might have something to do with mosquitoes, but, as it turns out, Swatting is the act of falsely reporting a crime or emergency to law enforcement or emergency personnel. This new offense is a Class A misdemeanor unless the prosecutor can show that you’ve been convicted of this same offense in the past.

Texas legislators enacted several new criminal laws in the 2021 legislative session. Below, we highlight one of them – Swatting. Being from Texas, I initially thought this might have something to do with mosquitoes, but, as it turns out, Swatting is the act of falsely reporting a crime or emergency to law enforcement or emergency personnel. This new offense is a Class A misdemeanor unless the prosecutor can show that you’ve been convicted of this same offense in the past.

The 2021 Texas legislative session has now closed and there were several updates to our criminal statutes. Below are some of the more notable changes or additions to Texas criminal laws that took effect on September 1, 2021:

The 2021 Texas legislative session has now closed and there were several updates to our criminal statutes. Below are some of the more notable changes or additions to Texas criminal laws that took effect on September 1, 2021:

This was the 6th year for our law firm to offer scholarships. In honor of the sacrifices of our military veterans, we decided to that the scholarships should be connected to military service. The first scholarship is a $500 award for a

This was the 6th year for our law firm to offer scholarships. In honor of the sacrifices of our military veterans, we decided to that the scholarships should be connected to military service. The first scholarship is a $500 award for a

In January of this year, the Supreme Court of Texas heard arguments for

In January of this year, the Supreme Court of Texas heard arguments for

The short answer is Yes. According to both local and federal courts, what you say during a butt-dial phone call can potentially be used against you in court. In Texas, a hearsay exception makes those overheard statements admissible. In the federal system, these calls are viewed as having no reasonable expectation of privacy—since you did not take simple precautions to avoid this kind of situation, you cannot expect someone on the receiving end of the call not to repeat what they heard.

The short answer is Yes. According to both local and federal courts, what you say during a butt-dial phone call can potentially be used against you in court. In Texas, a hearsay exception makes those overheard statements admissible. In the federal system, these calls are viewed as having no reasonable expectation of privacy—since you did not take simple precautions to avoid this kind of situation, you cannot expect someone on the receiving end of the call not to repeat what they heard.

No, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals recently held that people do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the information (1) contained on the Bitcoin blockchain and (2) that you provide to cryptocurrency exchanges.1 The Court reached this decision through an analysis of the facts under the “third party doctrine” of Fourth Amendment jurisprudence. This doctrine is explained in further detail below.

No, the Fifth Circuit Court of Appeals recently held that people do not have a reasonable expectation of privacy in the information (1) contained on the Bitcoin blockchain and (2) that you provide to cryptocurrency exchanges.1 The Court reached this decision through an analysis of the facts under the “third party doctrine” of Fourth Amendment jurisprudence. This doctrine is explained in further detail below.

Prosecutors in Texas must disclose almost all of the evidence in their possession to the defense. Disclosure is the rule and not the exception in Texas.1 Section 39.14(a) of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure requires the prosecution to disclose anything that “constitutes or contains evidence material to any matter involved in the action. . .”2

Prosecutors in Texas must disclose almost all of the evidence in their possession to the defense. Disclosure is the rule and not the exception in Texas.1 Section 39.14(a) of the Texas Code of Criminal Procedure requires the prosecution to disclose anything that “constitutes or contains evidence material to any matter involved in the action. . .”2

In Texas, the answer is yes. The possession of marijuana is a crime in Texas, so if an officer smells marijuana emanating from your car, he has probable cause to believe a crime is being committed. With probable cause, the law permits the officer to stop and search your car— regardless of whether you consent.

In Texas, the answer is yes. The possession of marijuana is a crime in Texas, so if an officer smells marijuana emanating from your car, he has probable cause to believe a crime is being committed. With probable cause, the law permits the officer to stop and search your car— regardless of whether you consent.

Under the typical Texas liability insurance policy both the insurer and the insured have mutual obligations and rights. The insured pays a premium to their insurance company to protect against unexpected losses and claims. On the other hand, the insurance company has a duty to defend against claims covered under the policy and a right to control the defense of litigation should it arise.

Under the typical Texas liability insurance policy both the insurer and the insured have mutual obligations and rights. The insured pays a premium to their insurance company to protect against unexpected losses and claims. On the other hand, the insurance company has a duty to defend against claims covered under the policy and a right to control the defense of litigation should it arise.

As Fort Worth criminal defense attorneys, we are often asked by witnesses and victims what might happen if it comes to light that the story they told the police was not exactly true. We often see this in

As Fort Worth criminal defense attorneys, we are often asked by witnesses and victims what might happen if it comes to light that the story they told the police was not exactly true. We often see this in