Alford v. State – (Tex. Crim. App.) Feb. 8, 2012

Alford v. State – (Tex. Crim. App.) Feb. 8, 2012

Cecil Edward Alford was charged with evading arrest and detention. While being transported to jail, Officers noticed that Mr. Alford was squirming around in the back seat. Once at the jail, officers got Alford out of the car and searched the back seat. As was procedure, they had searched the back seat of the squad car before their shift started to confirm that there were no items in the back seat. After searching the back seat of the squad car following Mr. Alford’s transport to jail, officers located a clear plastic bag with pills inside and, directly under the bag, a computer flash drive (“thumb” drive). As the jailers were booking Alford in, one of the officers took the thumb drive and held it up to Mr. Alford asking what it was. The officer then asked, “Is it yours?” Alford claimed that it was. At the time the jailer asked the question, Alford had not been advised of his Miranda rights.

The legal question arising from this situation is whether Alford’s admission that he owned the flash drive could be used against him at his trial.

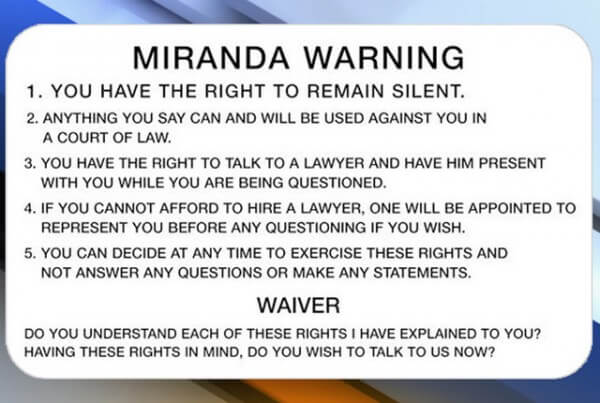

The Court of Criminal Appeals first analyzed this case by addressing custodial interrogation and the “booking-question exception” to Miranda. The Court recognized that questions “normally attendant to arrest and custody” or “routine booking questions” are exempt from Miranda. See South Dakota v. Neville, 459 U.S. 553 (1983); Pennsylvania v. Muniz, 496 U.S. 582 (1990). The CCA noted that Mr. Alford’s case hinged on whether the question that the officer asked him that night was reasonably related to administrative concerns or if it was a question designed to elicit incriminatory admissions.

The defense presented case law supporting the contention that a question does not necessarily fall within the booking-question exception to Miranda simply because the question was asked during the booking process. Specifically, the defense cited a footnote at the end of the Supreme Court’s opinion in Muniz that said, “recognizing a ‘booking exception’ to [Miranda] does not mean, of course, that any question asked during the booking process falls within that exception. Without obtaining a waiver of the suspect’s [Miranda] rights, the police may not ask questions, even during booking, that are designed to elicit incriminatory admissions.” Id at 602, n. 14 (Brennan, J., plurality op.)

The CCA conceded that case law actually supported both the State and the appellant in this case. Ultimately though, the Court held that the booking-question exception applies when the question reasonably relates to a legitimate administrative concern regardless of whether officer should have known that it might elicit an incriminatory admission. The Court held that the Officer’s question in Alford’s case had the legitimate interest of identification and storage of an inmate’s property and that the questions regarding the thumb drive did fall within the booking exception to Miranda.

Essentially, the court decided that the relationship between the officer and Alford was not the determining factor. Even though the Officer that asked Alford the questions was primarily responsible for the investigation, the Court still said that his question at the jail was just a booking question. To me, this case does not provide any clarity to the booking-question exception to Miranda. In any case, once a suspect is arrested, an officer could claim his questions are for booking purposes only, even when those questions are eliciting incriminatory admissions – and even if those questions are being asked while still in the field or at the scene.

This case just serves to reinforce what I’ve always advised folks – DO NOT SAY ANYTHING TO THE POLICE. Of course, there are times when talking with a police officer cannot hurt, but if you are under arrest, DO NOT SAY ANYTHING, DO NOT EVEN NOD YOUR HEAD, until you have been provided an attorney. If you must say something, say this: “I request an attorney and will not answer any questions until I have been provided an attorney.”